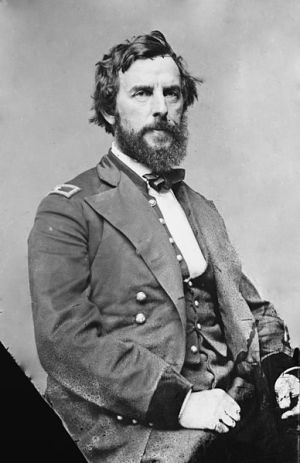

It’s funny how I will develop an interest in someone from the Civil War, especially some high ranking officer. It’s often the eyes that strike me the most. Or just that they’re damn fine looking gentlemen. I give you a wonderful example below of my two favourites…

If y’all follow me on Twitter, you know how much I love General Sherman and probably have picked up on how much I LOVE General John Reynolds as well. With Reynolds, it was totally the eyes that struck me the most and it turns out he was a pretty damn fascinating guy. You can check the post I wrote about him here.

It was much the same when I came across this handsome gentleman. Totally the eyes AGAIN. Y’all, meet Major General John Gibbon…

Of course I wanted to know more about him. Just as was the case with General Reynolds, Major General Gibbon is an interesting guy. I recently wrote a post about the Battle of South Mountain, in which Gibbon was a part of at Turner’s Gap. Check it out here.

On to more about Gibbon. Here we go…

John Gibbon was born on April 20, 1827 in Philadelphia, PA. When he was ten years old, Gibbon and his family moved to the Charleston, South Carolina. His father had accepted a position of Chief Assayer (basically, analyzing the quantity of gold, silver, etc. in a coin) at the U.S. Mint.

In 1842 at the age of 15, John was appointed to the US Military Academy at West Point. He had discipline problems (i.e. rebel, badass, etc) and ended up having to repeat his ENTIRE first year. Clearly, mistakes were made but lessons were learned. After this, his time there and, subsequently, his entire military career was defined by rigid discipline. He graduated in the middle of his class in 1847.Two of his classmates were Ambrose Burnside and Ambrose Powell Hill.

After graduation, John was made Brevet 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd US Artillery.

He was in Mexico during the Mexican-American war, but saw no action there. He was also in Florida and in Texas.

In 1854, he returned to West Point where he taught artillery tactics. This proved to be quite a fit for him and must have been something he enjoyed, because he ended up writing an ENTIRE book about it called the Artillerist’s Manual. It was published in 1859, and was adopted by the War Department very quickly. It ended up being used by both the Union and the Confederate Armies during the Civil War.

In 1855, Gibbon married Francis North Moale and together they had four children: Frances Moale, Catharine (Katy), John Jr. (he died as a toddler) & John S. Gibbon.

Life seemed to be rolling along smoothly for John when the Civil War broke out in 1861. His father, who still lived in the south, was a slave owner. John’s three brothers and his cousin, J. Johnston Pettigrew, all fought for the Confederacy.

John, who was stationed in Utah at the time, decided to remain loyal to the Union. He took the oath to the United States and reported to Washington. Here he was made Chief of Artillery for Major General Irwin McDowell.

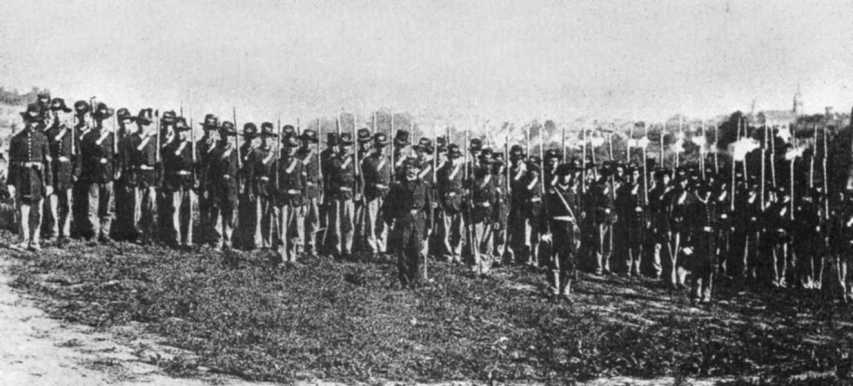

In 1862, the Gibbs (I know, so not an original nickname is you watch NCIS but…come on…it works! And it’s kinda cute…) was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers and placed in charge of King’s Wisconsin Brigade, made of men from Wisconsin (duh), Michigan & Indiana. He proved to be quite good at handling the volunteers, and, unlike other officers, he did not have a negative opinion of them. Not only was he big into drilling his soldiers but he used a rigid discipline system to turn them into being some of the most bad-ass, ferocious fighters in the Army of the Potomac. Gibbs believed the best way to promote such rigid discipline was using a system of awards (gold star, anyone?!) to recognize good behaviour and, for not-so-good behaviour, he used penalties that were meant to hurt their pride.

A few examples…

Fence stealing was popular (cause why not steal a fence when you’re a volunteer soldier, right?) amongst his brigade. Fence pieces would be used for shelter or fires. This extra curricular activity dwindled after Gibbs came on the scene. Fence stealing ain’t so much fun when you have to rebuild said fence.

On a positive note, however, the Gibbs discovered that giving the well-behaved soldiers 24 hour passes was a thing of miracles for promoting good behaviour. Y’all, this 24 hour pass was their version of a gold star. Leave camp, go have fun! I’d be good to if it meant I got to leave camp for 24 hours and go play cards (cards being a euphemism for various sorts of shenanigans I won’t mention on here) with the locals.

He also changed the uniform of the soldiers. The most notable of these changes was the hat. He replaced the traditional Kepi with the black felt Hardee hat. Soon after this, they became known as the Black Hat Brigade.

Clearly, Gibbs wanted his bad-ass Brigade to stand out.

And stand out his brigade did…

He fought at Second Manasses at Brawner’s Farm. This was one of the most intense fire fights of the entire Civil War. One of his solider’s remarked of him after the battle:

How completely that little battle removed all dislike from the strict disciplinarian, and how great became the admiration and love for him, only those who have witnessed similar changes can appreciate…

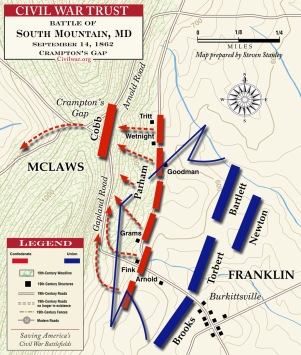

Gibbs was at South Mountain at Turner’s Gap. It was here that either General Joseph Hooker or G McC (my pet name for General McClellan) christened Gibbon’s brigade as the “Iron Brigade”. The men had “fought like iron”.

At Antietam, the Iron Brigade had heavy losses. It was here that Gibbon manned an artillery piece during the very bloody fighting in the Cornfield.

In late 1862, John was promoted to the 2nd Division, I Corps. This meant he would be separated from his “Iron Brigade”:

My feeling was one of regret at the idea of being separated from my gallant brigade.

It is said that John Reynolds picked up on this and said he could offer it to someone else. Gibbs, despite qualms about leaving, did accept the new position he had been offered. One officer of the Iron Brigade described Gibbon as “a most excellent officer…beloved and respected by his whole command”.

His love of this brigade and its men evidently stuck with the Gibbs throughout his life. His answer to an invitation to all soldiers honorably discharged from Wisconsin shows how he felt towards them:

I was not a Wisconsin soldier, and have not been honorably discharged, but at the judgement day I want to be with Wisconsin soldiers.

So, on it was to his new command, and the first battle he led them at was Fredericksburg. It was here Gibbon ended up receiving a wound near his wrist after a shell exploded close by. This put him out of duty for several months.

He was back in time for Gettysburg. It was here he commanded the 2nd Division of General Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps.

On July 3rd at Gettysburg, Gibbon was at Cemetery Ridge. His major role in the battle was the repulse of Pickett’s Charge. In a council of war meeting (sounds like Game of Thrones shit happening here…) the night before, General Meade had pulled Gibbon aside and predicted that if Lee were to attack, it would be right where Gibbon would be. Eerily enough, Meade was right. Gibbon’s division did bear the brunt of the fighting, as predicted by Meade. Both Gibbon and Hancock ended up getting wounded here.

With being wounded, Gibbs was out of action and he ended up being sent to Cleveland, Ohio where he worked in a draft depot.

I’m sure that was really exciting…

But here’s something really cool. While Gibbon was still recovering from his wounds (okay, so that’s not so cool but this next part is the total silver lining in it all), he was able to attend the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863. Y’all know what happened on that day, right? GETTYSBURG ADDRESS BY MY FAVOURITE MAN. How awesome is it that Gibbon got to see and hear Lincoln give the Gettysburg Address? Also, could you imagine being there at the Gettysburg Address? Lincoln and Gibbon in the same place? I would have been fangirling big time. On a serious note, it would have been absolutely amazing to witness the Gettysburg Address, perhaps one of the most amazing speeches ever written (that’s for another post though).

Once he’d recovered from his wounds, Gibbon was back in action again. He dove right back in for the Overland Campaign and fought at Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. On June 7th, 1864, he was promoted to Major General for his service in the Overland Campaign.

On August 25, 1864, he and his men fought in the Second Battle of Reams Station. He felt his Division had fought poorly and this very much disheartened. At this time, he also began to quarrel with his superior, General Hancock. I’m guessing Hancock was probably not a good man to cross. Although promoted briefly to command the XVIII Corps, Gibbs ended up going on sick leave.

In January 1865 he came back and was given command of the XXIV Corps in the newly created Army of the James. James Rufus Davies, a member of the Iron Brigade, had this to say about Gibbon receiving this command:

His honors are fairly won. He is one of the bravest men. He was with us on every battlefield

On April 2, 1865, Gibbon was involved in the Third Battle of Petersburg. This battle was also known as (SPOILER ALERT) the Fall of Petersburg, so I think we all know how that turned out for the Confederates. It was during this battle that the Gibbs captured Fort Gregg, part of the Confederate defences.

During the Appomattox Campaign, Gibbon blocked the Confederate escape route during the battle of Appomattox Courthouse.

At the conclusion of the Appomattox Campaign, Gibbon served as the Surrender Commissioner.

After the Civil War, Gibbs was demoted to being a Colonel in the regular army (this apparently happened quite a bit. It’s complicated to get into and I’m just beginning to learn about it myself). Gibbon spent much time on the frontier. He was mainly engaged in the Indian Wars. It was Gibbon who came upon the remains of Custer and his men after the Battle of Little Big Horn.

In 1885, he was promoted to Brigadier General in the regular army. He was placed in command of the Department of Columbia, which represented all points of the Pacific Northwest. In 1890, he was made head of the Military Division of the Atlantic. He only held this post for a year, however, as he was forced to retire in 1891.

In all, he served nearly fifty years! John Gibbon passed away on February 6, 1896 in Baltimore, Maryland and he is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

One cool thing I learned in researching this post is that Gibbon has a few towns that are named after him. Thanks for my cool Twitter follower @AndersenTy, I found out there is a town in Nebraska called Gibbon. Yes, named after John Gibbon. There are others too – in Oregon, Minnesota, and Washington. Gibbon River and Falls in Yellowstone National Park is also named after him. Gibbon went there on an 1872 expedition.

Besides “The Artillerist’s Manual”, Gibbon also wrote two other books, both of which were published posthumously: “Personal Recollections of the Civil War” (1928) and “Adventures On The Western Frontier” (1994).

Just on the lighter side of things, apparently Gibbon was quite the colourful speaker, something which I appreciate because I do have a knack for use of colourful language myself (as I’m sure y’all have picked up on from some of my blog posts or videos). A member of General Meade’s staff described Gibbon as having an “up-and-down manner of telling the truth, no matter whom it hurt”. In other words, he was blunt. He could also out-swear most officers in the Army of the Potomac, which does make him a personal hero of mine now (upon finding this out, I blurted out “that is f&^%ing awesome!”). Apparently, the exception to this rule was Andrew Humphreys and quite possibly (and for some reason this did not surprise me), Winfield Scott Hancock.

Gibbon was a really cool, interesting guy. He was clearly well-respected by his troops and despite being a strict disciplinarian, a hard-ass and a-type about drilling his soldiers, in his heart he clearly cared about those he commanded. He created some of the most bad-ass fighters in the Army of the Potomac when he commanded the Iron Brigade. And the men he commanded after that were just equally as bad-ass. I’ll end this post by leaving you with a photo of the monument to Gibbon, which is at Gettysburg. It was dedicated on July 3, 1988 and it close to where he was wounded during Pickett’s Charge. Check out the swagger…

As always, thanks for reading! I hope y’all enjoyed this post. I certainly enjoyed researching and writing it.

Until next time,

Mary

__________________________________________________________

Sources

“John Gibbon”. Civil War Trust. http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/john-gibbon.html?referrer=https://www.google.ca/

“John Gibbon, Loyal and Able Soldier” http://www.armchairgeneral.com/forums/showthread.php?t=139325

Nolan, Alan T. “The Iron Brigade: A Military History” Indiana University Press: Indianapolis. 1961.

Reardon, Carol & Tom Vossler. “A Field Guide To Gettysburg”. University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.2013.

John Gibbon. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Gibbon